Species-rich semi-natural (high nature value, HNV) grasslands are a common product of humans, nature, and time. They are the jewels of our landscape, a fodder for our animals, and a pleasant place for our recreation. Why do they exist, and why are they so diverse? Where to find them? How do different groups of people perceive them? Do we have enough such grasslands, and will we have them in ten years? What can we do to preserve them? We strive to answer these and similar questions through our interdisciplinary research.

What are we researching?

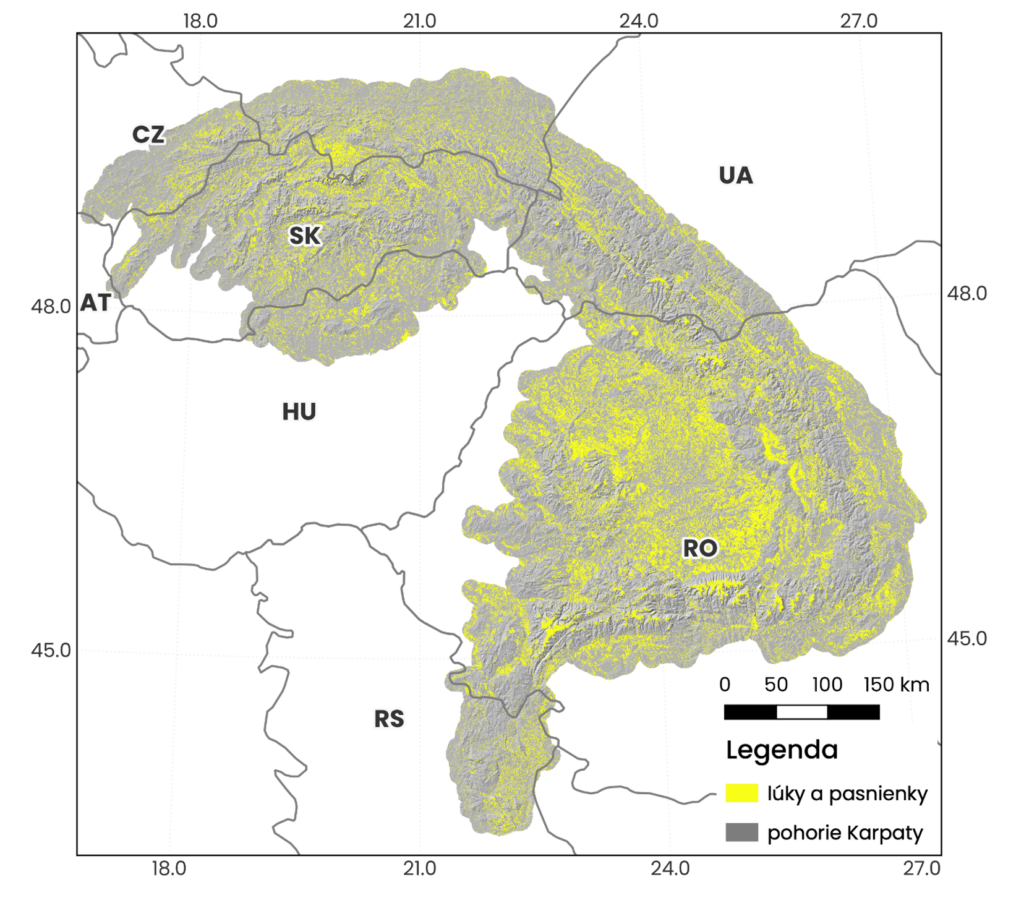

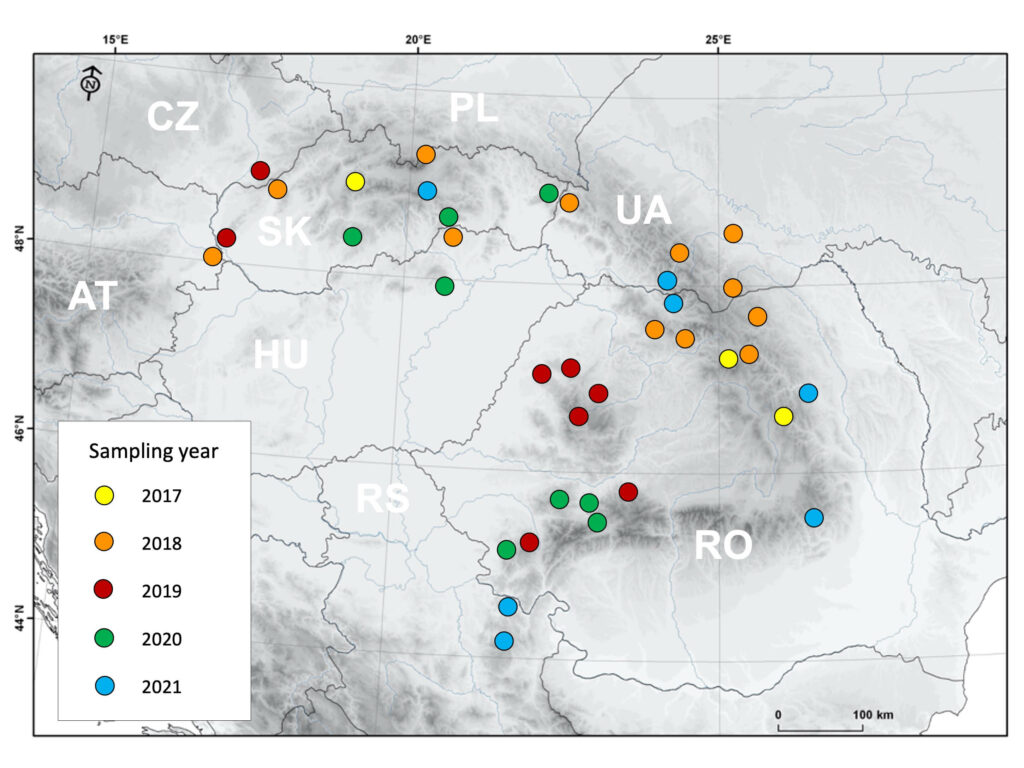

We are trying to determine what has supported, currently supports, and could support the species richness of semi-natural grasslands in Europe – in the past, today, and in the future. We focus primarily on grasslands in the Carpathians (Slovakia, Romania, Ukraine, Czech Republic, Austria, Poland, Hungary, Serbia), but we also collaborate on grassland research in the Alps.

Why are we researching it?

We consider species-rich grasslands interesting and valuable because:

- Species rich grasslands are part of cultural heritage – to many local people, including us, they appear beautiful and worth preserving because they were created by our ancestors and have shaped the character of the local landscape for centuries, evoking a sense of home.

- Biodiversity makes the landscape more resilient – a natural environment with more species can better withstand any impacts, whether natural or human-induced.

- Biodiversity makes the landscape more attractive for both humans and other life – more species mean more interactions between species and a more complex, stimulating environment, providing more opportunities for permanent residence or occasional visits.

- Products from traditional (organic) farming, which includes species rich grasslands, are often more valued by people, including us, as potentially healthier, tastier, and more beautiful compared to products from industrial agriculture.

- Preserving grassland biodiversity represents a pleasant and meaningful human activity, which has been gradually diminishing in rural areas. If rural life is to remain interesting, preserving species rich grasslands could significantly contribute to this goal.

How are we reasearching it?

We have joined forces across various scientific disciplines and aim to collectively leverage insights from previous research on plants, humans, and the landscape as a whole.

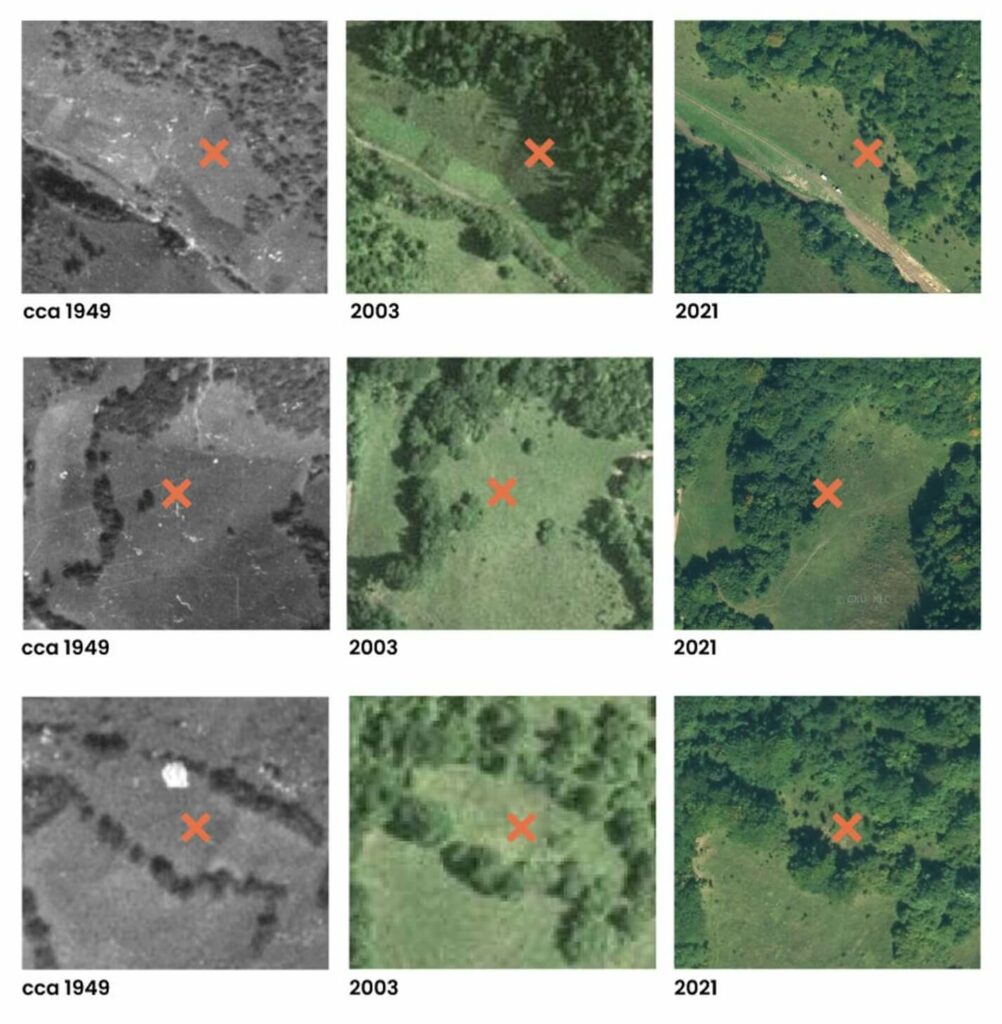

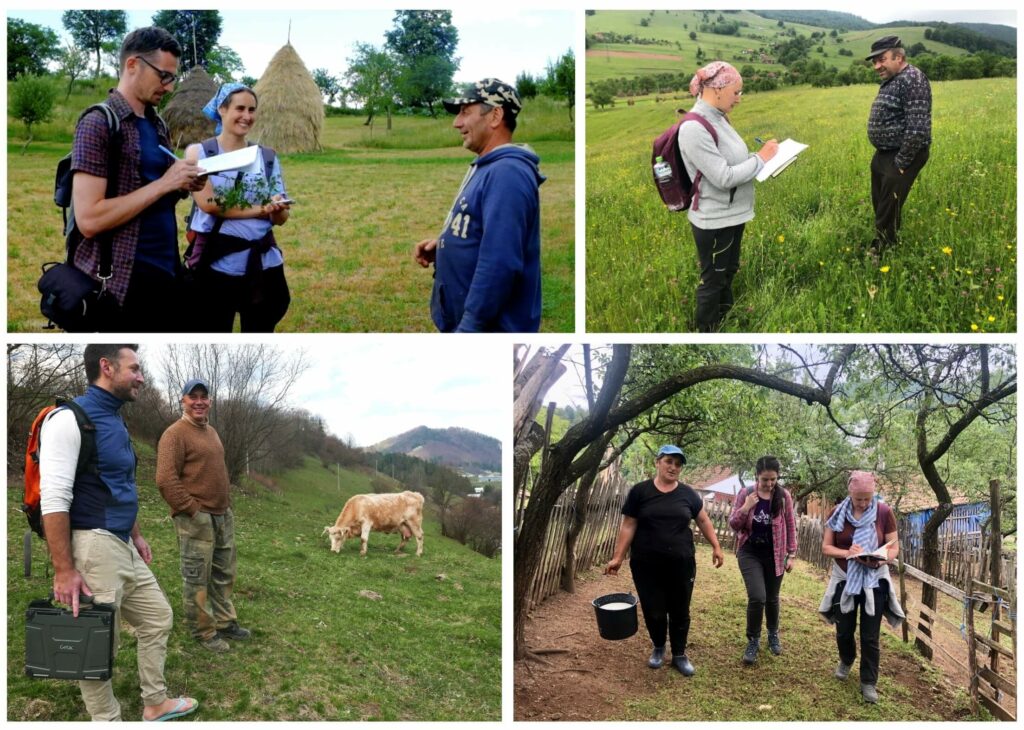

Within our team, botanists focus on studying the vegetation of hay meadows and pastures, including their surroundings (e.g., species composition on specific parcels, Fig. 1). Geographers gather and evaluate information about the physical nature of the local landscape, both current and historical (e.g., terrain configuration or changes in forest cover from aerial and satellite images, Figs. 2 and 3). Ethnologists and anthropologists collect information about local human activities and opinions that may relate to the nature of local grasslands and the landscape (e.g., information about which elements of subsidy schemes are challenging for farmers and why, based on interviews with them, Fig. 4). By comparing the evaluated information, we collectively strive to understand which circumstances promote grassland diversity, which, on the contrary, diminish it, and why.

Who funds our research and why?

We primarily seek funding for our research from public sources, both domestic and international, mainly supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency (APPV), the European Partnership for Biodiversity (biodiversa+), and the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and Slovak Academy of Sciences (VEGA, http://www.vega.sav.sk).

These agencies allocate a portion of taxpayer funds to research questions that are of long-term or current interest to people or whose answers could be useful in some way for practical purposes (applied research). For example, the Slovak Ministry of the Environment expects our applied research to help understand and better shape how to support management that can preserve or improve meadow and pasture diversity without negatively impacting local communities.

In the past, our research has also been supported by the National Geographic Society and the public (individual donors) through the GoFundMe project.

Does the research pose any threats, and how do we address them?

We are aware that all new scientific knowledge represents a certain kind of power. It is like a double-edged sword. While we strive to use the acquired knowledge primarily for the benefit of the studied communities, there is a risk that someone could misuse some of it – for example, insights into which economic approaches reduce species diversity or which elements of subsidy schemes are detrimental to farmers.

To minimize the possibility of knowledge misuse from our research, we have established strict ethical rules:

- We aim for what is called participatory research – we seek to involve representatives of people who may be affected by the results, so-called stakeholders, in all phases of the research, primarily including farmers, local authorities, other local residents, and relevant employees of affected offices, including ministries.

- We proactively engage in ongoing discussions with all stakeholders about how they perceive the research and how it should or should not proceed.

- We do not collect any non-public information about anyone without the consent of the affected people, nor do we disclose such information to any third parties (as independent academic institutions, we have no reporting obligations to any authorities or oversight bodies).

- All stakeholders have access to contact us, and we strive to answer all their questions about our research on an ongoing basis – see also these pages and the list of regularly updated answers to frequently asked questions below (FAQ).

- We strive to share all research results in an understandable form with all stakeholders.

What have we discovered so far?

Our interdisciplinary research has been ongoing since 2017. Initially, it focused primarily on countries where grasslands are still managed in a more traditional, low-input and low-intensity way (Romania, Ukraine). In Slovakia, we have conducted research in seven areas: Nová Bošáca, Liptovské Revúce, Nová Sedlica, Krupina, Silica, Vernár, and the surroundings of Bratislava.

We have found, for example:

- Carpathian grasslands are characterized by extraordinary species richness from a pan-European, and even global, perspective, especially in regions with preserved low-input agriculture without artificial fertilizers and cooperative large-scale farming. Natural conditions, such as geological substrate, diversity of the surrounding landscape, etc., contribute to increasing grassland species richness, but the management practices, both contemporary and historical, have a fundamental influence.

- In remote mountainous areas of Romania, Serbia, and Ukraine, numerous elements of historical agriculture have been preserved, such as spring grazing on hay meadows, transhumance to mountain pastures, fertilization with ash, etc. Cultural elements of local rural communities, such as festivities associated with driving sheep to mountain pastures, or with drying and storing hay, milk product production procedures, and other treasures of tangible and intangible cultural heritage, have also been preserved. We aim to document these values because it is only a matter of time before they are replaced by modern practices, as has happened in economically more developed regions of Europe.

- Traditional farmers, relying on the knowledge and experience of their ancestors, excel in the wealth of traditional ecological knowledge, which they apply to ensure the long-term preservation of the quality and quantity of their agricultural production. The focus on long-term goals typically leads to a sustainable approach that prevents soil and landscape overload and degradation, contributes to their rapid regeneration, and increases their resilience and adaptability in the face of environmental fluctuations.

- Spring grazing on hay meadows was once a common practice on all farms and in all regions of the Carpathians. After the spring grazing season (mostly on the feast of St. George, which falls on April 23-24 according to the Gregorian calendar and on May 6 according to the Julian calendar), the livestock was driven to mountain pastures. The decline of Carpathian shepherding, among other things, resulted in the disappearance of spring grazing and ultimately contributed to the shift in the timing of the first mowing of hay meadows several weeks earlier. As a result, many hay meadow species do not have enough time to regenerate generatively, leading to their decline and overall homogenization of hay meadow species composition.